On September 22, 1994, NBC aired the pilot of a new television sitcom called Friends. It began just as simply as the title suggests, with five twentysomething friends lounging at a coffeehouse, discussing mundane details about their personal lives. These people don’t even have names for the first few minutes. Then, out of nowhere, Rachel Green (Jennifer Aniston) bursts through the doors of Central Perk in a sopping wet wedding dress looking for her childhood friend, Monica Geller (Courteney Cox). She introduced herself to the gang, and the gang to all of us. The story began, and has ceased to end in our cultural imagination.

When Friends—developed by David Crane and Marta Kauffman originally under the titles Insomnia Café, Six of One, and Friends Like Us, before eventually going with simply Friends (prompting a name change in an ABC sitcom that had debuted just months before called These Friends of Mine, which was soon retitled Ellen)—was officially put on the NBC schedule in the fall of 1994, the network showed their confidence in the series and its cast of virtually unknown actors by giving them a prime spot in their coveted Thursday night lineup which would later be known as Must-See TV. Warren Littlefield, then president of NBC Entertainment, was looking for a new series that would “represent Generation X and explore a new kind of tribal bonding,” but that’s not exactly how the creators described it; David Crane would argue that Friends would not be a series targeted at one set generation, and wanted to produce a series that everyone of all ages would enjoy watching. In the long run, Friends would become just that. NBC’s famed Thursday night lineup that once included Family Ties (1982–1989), Cheers (1982–1993), and The Cosby Show (1984–1992) was now populated by three series set in New York City: Mad About You, covering the married angle; Seinfeld, exploring the eccentric/neurotic side; and Friends, which delivered the post-college, twentysomething experience. The advantageous spot on the fall lineup led Friends to pull in an admirable 22 million viewers in its first episode alone—aided without a doubt by its lead-in and follower on that night’s schedule, but also by promising reviews from critics. Variety found the actors to be “resourceful” with “sharp sitcom skills” but found that funnier writing would be needed going forward. Other critics said similar things but ultimately noted that the series’ ensemble cast would be the key to its success, lauding their comedic timing and chemistry with each other. Some critics would even later claim that Friends was television’s first real ensemble comedy—even though Seinfeld had a somewhat similar premise and was a self-described show “about nothing,” the key difference between the two was that Seinfeld was never afraid to make quirky, potentially offensive, or neurotic jokes even if the audience didn’t get them. Especially in the early years, David Crane and Marta Kauffman would obsessively monitor the studio audience’s reaction to every joke and rewrite as needed. Friends cared immensely about its audience, its premise, and never straying too far away from its comfort zone.

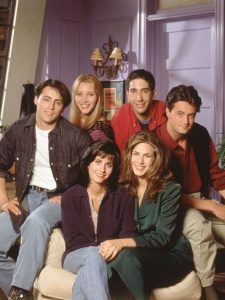

- One of the first official cast photos from the first season, 1994 (Source: NBC/Warner Bros.)

For all of their talent and chemistry, the cast of Friends was just that—virtually unknown. Crane and Kauffman had worked with David Schwimmer in the past and wrote Ross Geller specifically for him, and while he was hesitant to leave his theatre roots behind, he was the first character to be cast. Courteney Cox—who, at that time, was best known for a recurring role on Family Ties as well as the girl who gets pulled onstage in Bruce Springsteen’s “Dancing in the Dark” music video—had immediately expressed interest in Monica, but the producers thought she’d be better for Rachel. After her audition, though, it was clear that Cox was destined for Monica Geller. Lisa Kudrow, who had first decided she wanted to pursue a career as a microbiologist before turning her attention to acting, was best known for her recurring role as snooty waitress Ursula on NBC’s Mad About You, who was initially a no-name, one-episode bit role that ended up being a hit with audiences. The producers of Friends, including esteemed television director James Burrows, knew there was no question Kudrow was Phoebe Buffay. It wouldn’t be unheard of for a series regular actress to pop up in a recurring role on another series, but Mad About You and Friends were on the same network, the same night, and both set in Manhattan. It just wouldn’t work to have the waitress from Riff’s zipping downtown every night to live her double life as a West Village massage therapist. And so, Phoebe and Ursula were written as estranged twin sisters, and Ursula appeared on Friends several times throughout its run (Helen Hunt and Leila Kenzle also made cameos as Jamie and Fran from Mad About You in Ursula’s first episode of Friends during season one, during which they confuse Phoebe for Ursula at Central Perk). Matt LeBlanc auditioned for Joey and is said to have put his own spin on the character, portraying him as simple-minded with a big heart. Crane and Kauffman weren’t convinced at first, but the network was sold right away. LeBlanc’s biggest credit until that point was as Vinnie Verducci on Married…with Children, and he later appeared as the character in two short-lived spin-offs: Top of the Heap (1991) and Vinnie & Bobby (1992). When Matthew Perry was cast as Chandler, he had also been cast in a starring role on a Fox comedy called LAX 2194, about airport baggage handlers in the year 2194 in which he starred as the head baggage handler who had to sort through aliens’ luggage. It goes without saying that everyone knew that show didn’t have a big future, and once it fell through, he was free to be Chandler Bing. Jennifer Aniston, who was the last to be cast, had struggled to make a true breakthrough for several years and came to be known among the television networks as the “failed sitcom queen.” Her best known role at that point was as Jennifer Grey’s character in the television adaptation of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, which was quickly cancelled. While she had read for Friends, the producers were unsure if she was their Rachel. In the meantime, Aniston booked another starring role on a CBS sitcom called Muddling Through, which was shot in the 1993–1994 television season to air in the summer with the possibility of more episodes. By the time Crane and Kauffman decided they’d wanted Aniston for Rachel, and with Friends rumored to be TV’s next big thing around all the networks, CBS raised the stakes by picking up Muddling Through which would make Aniston unavailable for Friends. She begged the execs at CBS every day to let her go because she was dying to do Friends, but they assured her that it was their series that would make her a star, “not that friendship show.” Everyone at NBC knew that Aniston was Rachel, so they played hardball and offered her a contract CBS simply could not compete with. In September 1994, CBS aired the final episode of Muddling Through and cancelled it soon thereafter. Two weeks later, Friends debuted on NBC.

In her book I’ll Be There For You: The One About Friends, journalist and pop culture expert Kelsey Miller observes that Friends very quickly brought a sense of youth and togetherness to people’s lives and television sets, despite its often unrealistic premise. “These people use the term comfort food when talking about Friends,” she writes. “They refer to its lightness, its detachment from reality. They watch it because they can’t relate. It’s ridiculous! Six adults with perfect hair who hang out in a coffeehouse in the middle of the day? Who’s paying for those giant lattes? Friends, for them, is pure escapism.” But for others, the series became a representation of a society and culture probably much wiser than Friends itself—the series was enormously popular in the UK by the late ‘90s (which was partly the inspiration for Ross and Emily’s wedding in London in season four), and its popularity quickly grew in other countries and continents and often helped people learn English. For many, Friends was America—how they spoke, laughed, and acted. Friends is also said to have genuinely impacted the discourse of the English language, with a 2004 study at the University of Toronto finding that the characters used the emphasized word “so” to modify adjectives more often than any other intensifier. Although the preference had already made its way into the American vernacular, usage on the series may have accelerated the change.

“Friends has managed to transcend age, nationality, cultural barriers, and even its own dated, unrelatable flaws,” says Miller. “Because, underneath all that, it is a show about something truly universal: friendship. It’s a show about the transitional period of early adulthood, when you and your peers are untethered from family, unattached to partners, and equal parts excited and uncertain about the future. The only thing you have is each other.” This can, perhaps, explain the series’ immense popularity among the Millennial generation—after all, Friends was initially about Generation X; a generation typically marked by characteristics of aimlessness and lack of goals. They were the first real generation to be raised by divorced and working parents (hence the term “latchkey generation,” since these children were generally unsupervised before their parents returned from work), which is said to contribute to said factors. All of the characters on Friends were supposedly reflective of twentysomething life in Generation X. But since the series’ popularity has continued to transcend both space and time let alone generational gaps, the uncertainty of careers and goals are even more prevalent among Millennials than they were with Generation X—which perhaps explains the enduring resonance of Friends among young people.

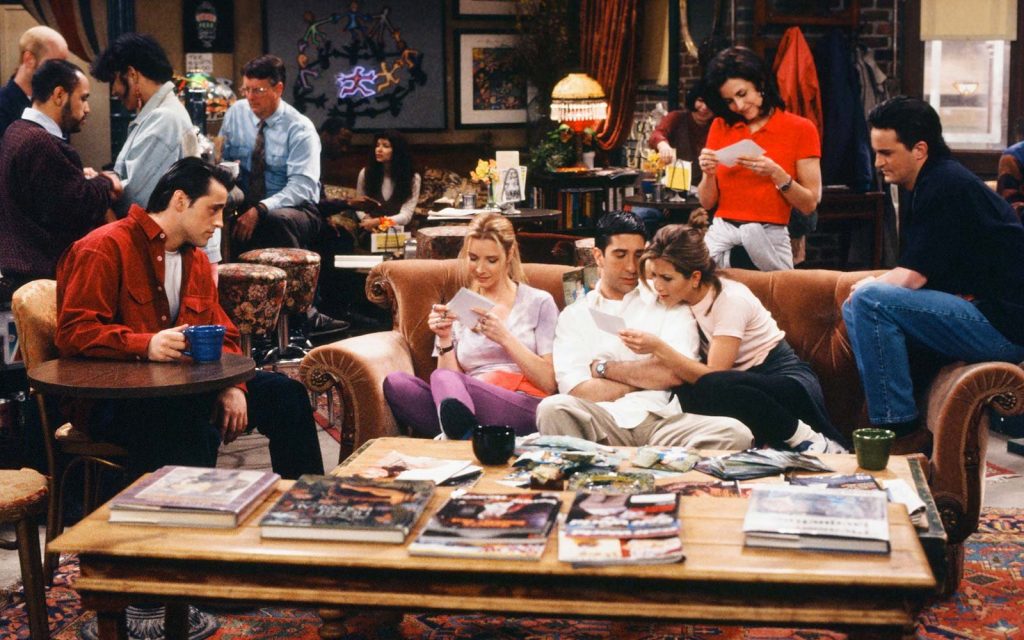

- The gang at their hangout, Central Perk, during the first season, 1995 (Photo: NBC/Warner Bros.)

The series’ near-instant popularity, especially while apart of the Must-See TV lineup on NBC, fit perfectly with the newfound approach to celebrity and tabloid media, which only boosted Friends’ exposure in the mainstream. “Friends had come of age during a period of rapid growth in celebrity entertainment journalism,” Miller writes. “Outlets like Premiere and Entertainment Weekly reported industry news for a mainstream readership, and now behind-the-scenes drama was as watchable as a show itself … It was the beginning of the ‘Stars Are Just Like Us’ era, when consumers were less interested in seeing actors at their most glamorous and untouchable, and more eager to see them taking out the garbage … From the beginning, Friends had played well with the press, embracing this blurry line between celebrity and character.” Elaine Lui (best known to her readers as Lainey), entertainment journalist and gossip media expert, believes that one of Friends’ crucial selling points was that we believed they were friends, both onscreen and off. “You’re feeding the illusion that what we’re watching every Thursday night is actually how they are in real life. That’s compelling.” And for the first few years, the producers and network used it to their advantage. The six main cast members appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show in 1995 after the conclusion of the first season (during which she cheekily asked them when they are getting a black friend; the first of many jabs to come at Friends’ infamous lack of diversity), and the crowd went nuts. Soon after, they appeared in Rolling Stone, and by the time the second season arrived, the producers and NBC knew they not only had a new hit on their hands, but potential at a future cultural touchstone. Aniston’s hairstyle, dubbed “The Rachel,” became a global style trend. The culmination was also the large amount of celebrity guest stars, with everyone from Marlo Thomas, Tom Selleck, to Brooke Shields, as well as the infamous “The One After the Super Bowl” episode (which famously included movie star appearances by Julia Roberts and Jean-Claude Van Damme), which received polarizing reviews at the time for being too much—the Chicago Tribune dubbed the episode “The One Where the Show Crosses the Line from Promiscuity into Prostitution.” The network, producers, and stars of Friends had to agree—it was too much. And for the remainder of the series, it became everyone’s mission to find a happy medium between using the series’ immense popularity and cultural relevance for financial gain and mainstream exposure, and providing loyal viewers with the laughs and stability they relied on every week for a decade. And despite any creative low points, Friends achieved that and more—it was ambitious at times but never crossed the line, and remained endearingly devoted to its premise and its characters. The cast famously stood as one behind the scenes, boldly telling the network and producers it was all of them or none of them. They all knew they were the collective stars of the series and didn’t want one cast member to rise above the others. They knew what they had and what they needed to preserve it, and it’s undeniable that it led to Friends’ endearing success.

Miller also pinpoints the events of September 11, 2001 as the moment when Friends was solidified as the ever-present and highly beloved television comedy we now know it to be in our popular culture. She writes that it wasn’t easy for anyone involved to figure out how to go on after the 9/11 attacks—considering Friends was both one of the most popular programs on television and took place in lower Manhattan—making it almost virtually impossible to not acknowledge it. But everyone soon realized that it wasn’t Friends’ job to acknowledge it, at least in that way. They learned very quickly that, following such a tragic and traumatic event that not only changed the course of history in the United States but also the rest of the world, people suddenly returned to things that had been a constant as a form of comfort in such a traumatic and uncertain time. By 2001, digital news and media had begun to plot its takeover, but print and television news ratings boomed following 9/11—as did primetime television programs that people had once relied on for a good dose of laughs. Miller reports that Friends viewership and overall investment had begun to dwindle by the end of season seven in 2001, and there were questions of how much longer the series would last. But by the time Friends returned for season eight that fall, following 9/11, ratings were through the roof again, just as they’d been in the early years. The eighth season even saw a dose of Emmy nominations to go along with the high numbers. It was at this point that Friends was solidified as the television equivalent of comfort food; a way of truly ignoring reality for a half-hour for the sake of our sanity. Lisa Kudrow said it best. “We’re not curing cancer. It’s not a big deal. But you know what? It is a big deal when you can offer people a break from such a devastating reality.”

- Ross' ex-wife Carol (Jane Sibbett) and her partner Susan (Jessica Hecht) at their wedding in season two: the first lesbian wedding on broadcast television, 1996 (Photo: Warner Bros.)

It would be hard to discuss Friends’ enduring legacy and resonance without also acknowledging its dated, problematic elements—which also happens to surround much of the contemporary discourse surrounding the criticism and ever-growing popularity of the series. Miller acknowledges the series’ vast tendency for gay jokes, especially among the guys (but also the girls, too; the tone in which Monica would criticize Chandler’s feminine qualities was always a bit harsh), but claims that Friends can’t be considered overtly homophobic given “The One with the Lesbian Wedding” in season two, in which Ross’ ex-wife Carol (Jane Sibbett) and her partner Susan (Jessica Hecht) get married—though it was likely a civil union or commitment ceremony in technical terms; same-sex marriage was light years away from legalization in the United States in 1996. Despite its other pitfalls, the lesbian wedding episode was remarkably well done for the mid ‘90s (particularly the bit where Ross walks Carol down the aisle after her parents refuse to attend). Still, I wouldn’t give Friends the label of not homophobic—it was far from it. It might not have been overtly homophobic, but jokes surrounding masculinity were a mainstay on Friends (and are still common on more contemporary comedies, such as Modern Family). Ross’ masculine panic surrounding his son having a Barbie is a particular highlight, especially when everyone around him doesn’t really seem to see the big deal. The episode ends with Monica exposing her brother’s habit to dress up in their mother’s clothing and have tea parties when he was a child, giving the episode’s themes an ironic touch—which was always Friends’ specialty. But we still can’t forget many of the series’ dated and problematic elements (and thanks to its continuing popularity and the Internet, we won’t have to). What sticks out in my mind the most is Chandler’s dad. “Of all the so-called dated storylines on Friends, this one most clearly marks it as a product of its era,” writes Miller, “that era being one in which transgender was not a word most people knew. Transphobia was not a touchy social issue because most people hadn’t even heard of it. Today, the trans community remains one of the most at-risk populations in the world, but in 2001, it was virtually invisible. The fact that Friends made such a big, flashy, nonstop joke of it was hardly controversial at the time. It was nothing like the lesbian wedding, which had been handled with enormous caution.” Within the storyline, when Monica finds out Chandler didn’t invite his father to their wedding, she insists on flying out to Las Vegas to invite him in person—where the man in question had been said to star in a gay burlesque show. But that’s just the thing, Chandler’s dad was no longer a man—when we meet the character, “he” was portrayed by Kathleen Turner, whose famous husky voice was apparently enough to sell the idea that the character was once a man. The producers had initially wanted to get Liza Minnelli to play Chandler’s infamous father, as the original idea (which probably would have aged better than what they ended up going with) was to make Chandler’s dad “the best female impersonator ever,” and then cast the actual iconic performer in the role. But neither Minnelli nor the others they approached felt comfortable playing an impersonator playing them. So they instead decided to look for a big-name actress to fill the role of Charles Bing—a.k.a. Helena Handbasket.

- Kathleen Turner as Chandler's father, a transgender woman known in her Las Vegas burlesque show as Helena Handbasket, 2001 (Photo: Warner Bros.)

“How they approached me with it was, ‘Would you like to be the first woman playing a man playing a woman?’” Kathleen Turner told Gay Times in 2018. “I said yes, because there weren’t many drag/trans people on television at the time.” She added, “I don’t think it’s aged well…but no one ever took it seriously as a social comment.” They really didn’t, and it wasn’t intended that way. But still, it’s hard to not wince watching the episodes with Turner as Charles/Helena with everyone making a mockery of his/her identity. From everyone’s insistence on using he/him pronouns when the character is clearly a woman, to Chandler’s mother Nora (Morgan Fairchild) still calling him/her Charles, to the icing on the cake—when Monica asks Rachel to keep an eye on Chandler’s dad at the wedding rehearsal dinner, saying “he’s the man in the black dress.” But just as Turner said, it was never intended as a social comment. If anything, it was probably supposed to be an extension of the gay visibility the producers had first attempted with Carol and Susan. Somehow, at the time and even now, it was better than nothing. “‘Better than nothing’ came up a lot in the interviews I conducted for this book,” Miller says. “I spoke with a number of people about the representational issues, lack of diversity, and all those elements that make the show dated (as we politely put it). To be honest, I expected more outrage. The Internet is packed to the gills with hot-take opinion pieces, as well as thoroughly researched academic papers about how problematic Friends is—how quickly it went for the cheap jokes, how rarely it featured minority characters, and on the rare occasions that it did, how poorly those characters were treated. But when I spoke to people one-on-one, there was very little vitriol … No one cited lack of diversity or homophobia as the primary reason they were turned off by it … The general consensus was that TV in that time was not a sophisticated or inclusive landscape, and in some ways Friends was better than its peers. By season seven, Carol and Susan had pretty much disappeared from the show, but the fact that they’d been there at all was something. Okay, the Hanukkah episode was a little bit silly and Santa-fied, but you know what? Better than nothing.” Against all odds, Friends continues to transcend any and all flaws and continue to endure and resonate among legions of audiences worldwide since, at its core, it’s about one thing we can all relate to at one time or another, regardless of age, background, ethnicity, or sexuality: friendship.

The series’ legacy continues to the present day and cannot be understated. In 2007, Time magazine included it among its list of the 100 Best TV Shows of All-Time and wrote, “It wasn’t just the sharp writing or the comic rapport that made Friends great. Its Gen-X characters were the children of divorce, suicide, and cross-dressing, trying to grow up without any clear models of how to do it. They built ersatz families and had kids by adoption, surrogacy, out of wedlock or with their gay ex-wives. The show never pretended to be about anything weightier than ‘we were on a break.’ But the well-hidden secret of this show was that it called itself Friends, and was really about family.” While the series might have technically concluded in 2004 after ten seasons, it didn’t really feel like it ever ended—international syndication of Friends continues to boom, leading it to feel like it was on virtually non-stop on every North American cable outlet for the last two decades (which it practically has been). The series also saw yet another new boom in popularity after Netflix acquired the streaming rights to all ten seasons in 2015, introducing Friends to yet another generation of young people who continue to rejoice in the relatable half-hour break from reality. In fact, the series is so popular on Netflix that when the streaming service announced their decision to phase out Friends from their platform late last year, the backlash and outcry from diehard fans on social media was such a force that the service decided to spend an extravagant amount of money to renew their streaming rights agreement with Warner Bros. to keep Friends on Netflix. As of this writing, Friends generates approximately $1 billion each year in syndication revenue for Warner Bros.

- The only public reunion of the actors since the conclusion of Friends in 2004, at an NBC tribute special to director James Burrows in 2016 (Photo: Getty Images)

The cast moved on and, as could only be expected, all have been successful in the years since Friends. David Schwimmer turned his attention to directing, did some movies, guest spots, and voice work, and returned to theatre and Broadway. Courteney Cox was offered the role of Susan Mayer on ABC’s Desperate Housewives, but turned it down due to her pregnancy. She too did some independent films and voice work before starring in a sitcom of her own on ABC, Cougar Town, which ran for six seasons and on which several of her Friends co-stars appeared in guest spots. Lisa Kudrow, who had already established a growing film career while on Friends, went on to co-create and co-produce the HBO comedy series The Comeback, shot from the perspective of a new reality show about a B-list sitcom star making her television comeback. The series was cancelled after one season in 2005 but Kudrow’s performance was particularly lauded, leading not only to Emmy nominations but to its eventual status as a cult hit with audiences as well as its eventual return for a second season on HBO in 2014. Amid several supporting roles in successful films, Kudrow also produced and starred on Showtime’s Web Therapy (2011–2015), which also saw appearances from several Friends co-stars. Matt LeBlanc continued his role as Joey Tribbiani on a Friends spin-off on NBC, Joey, which ran for two seasons until 2006. Thereafter, he began a hiatus from acting until he began portraying a fictionalized version of himself on Showtime’s Episodes (2011–2017), for which he received four nominations for the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Comedy Series. He currently stars in the lead role on the CBS sitcom Man With a Plan. Matthew Perry also appeared in supporting roles in several successful films as well as several attempts a television sitcom comeback, with short-lived series such as Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip (2006–2007), Mr. Sunshine (2011), and Go On (2012–2013), none of which seeing more than a single season. His most successful television comeback would be on the CBS remake of The Odd Couple (2015–2017), which ran for three seasons, as well as a recurring role on the CBS legal drama The Good Wife. One might refer to Jennifer Aniston as the most successful Friends cast member, who has since become a bonafide film star who has done little television since the end of the series. Aniston, like Kudrow or Schwimmer, began establishing a film career while on Friends in the late ‘90s but didn’t see as much success. It’s considered a difficult transition to make from the small screen to the big screen, especially when you’ve become as popular as Aniston was on Friends. Several critics note her performance in the 2002 independent film The Good Girl as the moment when Aniston proved she could in fact break free of her girl-next-door image as Rachel, and critics also acknowledge that she has since spent the better part of a decade since then pursuing roles that were very unlike Rachel (Horrible Bosses, We’re the Millers, or Cake), while also still appearing in a variety of 2000s romantic comedy films that we perhaps best remember Aniston for in our public conscious today (Along Came Polly, The Break-Up, He’s Just Not That Into You, or The Switch, to name only a few).

Of all the questions asked since the end of Friends and its rise in syndicated reruns and on streaming services, “when is a reunion happening?” seems to be the most popular, and is practically unavoidable for any of the stars in any interview. Rumors of a Friends feature film first began to escalate following the success of the Sex and the City movie in 2008, but Warner Bros. quickly debunked that theory. If anything, the buzz around a reunion has only grown in recent years, especially since network television has been giving revivals to popular sitcoms from the ‘80s and ‘90s, including Will & Grace, Roseanne, and Murphy Brown. “I mean, something should be done,” Lisa Kudrow said on Conan in 2018. “I don’t know what. They’re rebooting everything. How does that work with Friends, though? That was about people in their twenties, thirties. The show isn’t about people in their forties, fifties. And if we have the same problems, that’s just sad.” Some series have been worthy of their reboots, especially in the current stormy political times—Will & Grace returned in 2017 for a new perspective on women and gay men in the Trump era. Roseanne returned in 2018 and was remarkably relevant in our contemporary culture—polarizing as it was, Roseanne’s themes of class, economic status, and politically divided families were just as needed in 2018 as they were in 1988. Friends has no such hook. The series itself may seem timeless, but only because it was a representation of people and their lives at a certain age. “It’s about them then,” says Miller. “From a storytelling perspective, it would be close to impossible to reunite these characters—for the exact same reasons it’s so hard to reunite the actors. They have new jobs and families and they live in different cities. It would take some big life event to bring the characters back together, and now that the weddings and babies have been had, all that’s left are funerals—and no one wants to see that.” For more than a decade, the answer has been a consistent and firm no. “Someone asks me every day,” Marta Kauffman said in 2015. “I don’t get upset. I understand that people want to relive that. But you can’t relive that. We can’t go back to that time in our lives.” She also said, “Let’s be honest, reunions generally suck.” David Crane explained, “We ended right. It felt right… I think all the people who say, ‘Oh, I want to see them again!’ You really don’t. And I think they would turn on us on a dime.” Crane’s advice to those who never stop pining for a reunion or revival? The story has been told, from beginning to end. If you want to revisit it, it’s all right there for you, in reruns and on Netflix. “Watch those! We did it!” Still, the general consensus among the actors and the public is you never know. “Anything is a possibility,” says Jennifer Aniston, but Matt LeBlanc put it best in 2017. “That show was about a finite period in people’s lives. And once that time’s over, that time’s over. I went through that period in my own life. And when I revisit people from that time, it’s not the same. It’s just not. You can never go back, you can only move forward.” Some things belong to the past and aren’t meant to come alive again in the future. Friends belongs to a different era that we can still happily relive in reruns. It will continue to live on in our collective memory as a time in everyone’s lives—no matter what race, background, ethnicity, or sexuality—that most people can always relate to: your job’s a joke, you’re broke, but your friends are your family, and they’re always there for you. And for those of us who need that kind of reassurance in real-life from time to time, Friends is always there for us.

No comments:

Post a Comment