This June marks 50 years, an entire half-century, since the death of beloved performer and icon Judy Garland. It also marks 50 years since the Stonewall riots—an uprising that occurred at the Stonewall Inn in Lower Manhattan, then an infamous underground gay bar, where a seemingly normal police raid occurred in the early hours of June 28, 1969. Since homosexuality was still illegal as well as considered deviant social behavior and a recognized mental illness at that time, police raids of known gay bars were routine and brutal. But this time was different; the patrons didn’t go quietly. In fact, they fought back, and they fought back hard—so hard that the night in question is now considered to have singlehandedly jumpstarted the modern gay rights movement that have brought us our contemporary battles for LGBTQ equality. The link between Judy Garland and the Stonewall riots may not seem clear to all readers, but it’s an important and controversial one—and a link that remains relevant and still matters today.

Although Judy Garland is best remembered for roles in a variety of MGM musicals throughout the 1930s and 1940s, most of her lifelong personal struggles began with the film studio. Even though Judy was always of a healthy weight, MGM always insisted she was too fat to be a star and her appearance and image was constantly manipulated by film executives, which significantly impacted her self-esteem (studio boss Louis B. Mayer infamously referred to her as his “little hunchback”). Diet pills, combined with amphetamines that the studio forced many of their young actors to take to fulfill nearly impossible work demands, is believed to have severely contributed to Garland’s lifelong struggle with drug addiction. In addition to being completely reliant on prescription medication, Garland was plagued by self-doubt into her adulthood, and despite groundbreaking professional success, she needed constant reassurance that she was talented and attractive—all of which is generally thought to have been caused by her early days at MGM.

Although Garland saw further professional success in her later years, including an Academy Award-nominated performance in the Warner Bros. remake of A Star is Born in 1954, record-breaking concert appearances, a successful run as a recording artist with Capitol Records, her own Emmy-nominated television variety show, and sporadic film appearances for the remainder of her career—it’s arguable that her dismissal from MGM in 1950 left her career tainted for the remainder of her life. Patriarchal interpretations of her unreliability and erratic behavior combined with her own lack of control with alcohol and substance abuse made it practically impossible for her to replicate the success she saw with MGM as a child and young adult, despite the fact that she always had numerous celebrity friends and supporters to come to her defense. Her struggles with drugs and alcohol let alone a list of failed marriages became legendary, paving the road for her multiple momentous comebacks.

From the time she was a bankable star in countless MGM musicals, Garland had resonated with gay men. Her campy performances and musical numbers laid the groundwork, but it would be her personal and professional struggles that knocked her down more times than anyone could count that would make her a bonafide gay icon—and the fact that she kept standing back up after being knocked down resonated profoundly with an LGBT community which had no fundamental rights, were considered mentally ill, and driven underground. In the years before being openly gay was even remotely available, Judy Garland was already an icon and a symbol of strength and resilience for the gay community. She even inspired the term “Friend of Dorothy”—gay slang that dates back to World War II as a way for closeted homosexual men to identify each other without openly discussing sexual orientation. The term refers to Judy’s most iconic performance as Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz (1939), a character who has been critically and socially interpreted as being warmly accepting of those who are different.

- Judy Garland was hardly the first ever gay icon—Marlene Dietrich had already summoned her own queer icon status in the 1930s for her androgynous costumes—but her popularity and appeal to alternative communities managed to impact mainstream popular culture in a way that Judy’s predecessors had not. The first time Garland was referred to as a gay icon in mainstream media was in Time magazine in 1967, which reviewed her concert series at the Palace Theatre in New York City that year. They noted that a “disproportionate part of her nightly claque seems to be homosexual” and that “[t]he boys in the tight trousers” would “roll their eyes, tear at their hair and practically levitate from their seats” during Garland’s performances. In a nutshell, Judy’s appeal with gay audiences boils down to her being a tragic figure, which not only resonates with gay men but they identify with it, too.

- “Homosexuals tend to identify with suffering,” wrote novelist William Goldman in an Esquire article also from 1967. “They are a persecuted group and they understand suffering. And so does Garland. She’s been through the fire and lived – all the drinking and divorcing, all the pills and all the men, all the poundage come and gone – brothers and sisters, she knows.” He also suggests that if gay men have one enemy, it’s growing older, and Judy Garland represents “youth, perennially, over the rainbow.” Garland enthusiast and superfan Scott Brogan, who has run the popular fan site The Judy Room since 1999, maintains that it was not only her value as a tragic figure whom gay fans could relate to but many are also captured by her enormous talent and performance ability. “Her highs were really high, and her lows were really low, and yes, she did have a tragic life in certain respects, but it comes back to her voice and her performances,” he said. “To call Judy Garland an icon of the gay community is a massive understatement,” says Tina Gianoulis in The Queer Encyclopedia of Music, Dance & Musical Theater. “Garland’s fragile but indomitable persona and emotion-packed singing voice are undeniably linked to modern American gay culture and identity. This is especially true for gay men, but lesbians are also drawn to identify with Garland’s plucky toughness and vulnerability.”

- By 1969, Garland had reached a point of financial despondence—having been sufficiently incapable of managing her own finances, she kept a gruelling worldwide concert schedule as a result, which did not bode well with her decreasing health caused by her never-ending reliance on alcohol and prescription medication. That June, she was found dead of a barbiturate overdose at a rented home in London at age 47, and her funeral was held in New York City on June 27. Meanwhile, later that evening at the Stonewall Inn in Lower Manhattan, a series of LGBTQ individuals bravely resisted arrest, badgering, and torture at the hands of homophobic society, and the modern gay rights movement was born. It has long been suggested that Judy Garland’s death and funeral the day before had caused such a state of despair that the gay community finally found the strength to fight back—but whether this theory has any factual basis has long been called into question and become rather controversial among many LGBTQ historians.

- The “Judy myth,” as Perry Brass from Philadelphia Gay News puts it, is just that—a myth. “The Judy Garland myth, I’ve always felt, was the most pernicious of them all. Basically, it said that it took Garland’s death to make LGBT people angry enough to fight back. That was not true,” he wrote. “We had been fighting back all along; there were numerous instances of us doing so against huge odds … Power did not come from the streets then as we later felt, when gay groups joined other identity groups and seriously organized. What the Judy myth did was make many older, ‘bourgeois’ gay men, lesbians and their allies feel comfortable. If what happened at Stonewall was outside their comfort zone — and for many it was — they could feel all gooey and happy knowing the ‘girls’ were driven to this by some of the feelings they had: sadness over the death of Mickey Rooney’s girlfriend in those sweet 1930s musicals from their youth.” Gay Liberation Front founder Bob Kohler, who died in 2007, knew many of those who took part in the now-legendary riots that weekend, and he too angrily dismissed the Garland hypothesis, saying, “The street kids faced death every day. They had nothing to lose. And they couldn’t have cared less about Judy. We’re talking about kids who were fourteen, fifteen, sixteen. Judy Garland was the middle-aged darling of the middle-class gays. I get upset about this because it trivializes the whole thing.” Scholar and historian Mark Segal echoes that the myth trivializes the oppression their community was fighting against, calling it a “disturbing historical liberty” that is “downright insulting to the [LGBTQ] community.” Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, one of the few remaining Stonewall riot participators who is still alive, agrees that Garland’s death inspiring the riots is likely untrue, but laments that the theory has become so powerful and widely spread that it seems useless to continue trying debunking it. “There are people who connect [Garland’s funeral] to the narrative of Stonewall, and you’re not going to tell them it doesn’t connect, so let them have it,” he told The Washington Post in 2016. “It didn’t start the riot off, believe me.” He also suggests that the rioters would have most likely been apart of R&B and rock music scenes and would not have listened to the easy-listening showtunes of Judy Garland.

|

| Judy Garland as Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz (1939). The character became the inspiration for the gay slang "Friend of Dorothy," a term dating back to World War II as a way for gay men to secretly identify themselves. (Photo: MGM) |

- Although the overwhelming consensus is that Garland’s death itself most likely had very little to do with the riots that inspired the modern gay rights movement, many other historians and critics are not so quick to devalue the involvement of the icon’s death in the famous uprising. “I think that there were people there who were upset [by Garland’s death], but it was more than just one thing,” says Scott Brogan. “Sure, a lot of the street kids probably didn’t really care that much. But I think we shouldn’t count out the fact that Judy’s death did play a part. It wasn’t the only reason, of course, but there still were a lot of people there who were just … their nerves were shot.” Tina Gianoulis also acknowledges the ambiguity surrounding the “Judy myth,” but laments that the story has “such poetry that one feels it ought to be true.” In a now-deleted article commemorating the 40th anniversary of both the Stonewall riots and Garland’s death in 2009, culture critic Jeff Weinstein said that some of the imagination surrounding Judy’s death being the inspiration for the riots “seems credible,” since Garland’s life was also a battle cry for being free to love. “Yes, Judy was responsible for Stonewall, the way flowers are responsible for spring,” he wrote. “Of course, her life was a mess. Like opera counterpart Maria Callas, young Garland was an ugly-duckling diva left in the lurch by family and men. Employer MGM (and before that, maybe her mom) hooked her on drugs. Later, she was a time-bomb on the set – when she managed to show up.” He also states that he believed Judy possessed a rare quality that other performers lack, where she was able to perform in film or on stage as “Judy herself” and it is this authenticity that has allowed her to continue resonating. “I never could say exactly what that something is, but I’m convinced it’s close kin to the spirit of the brave and furious queens who taunted New York’s boys in blue with a kicking chorus line, to the tune of ‘It’s Howdy Doody Time’ … They also wore their hearts on their sleeves, whatever those sleeves were attached to. Just like Judy. Forty long years later, I remain grateful to them all. There’s still plenty of singing, and kicking, left for us to do.”

An overarching question that remains surrounding Judy Garland and the gay rights movement is not whether she still resonates, but whether her cultural impact and vast talent will be forgotten by future generations of gay men. When Jeff Weinstein compared Judy in The Wizard of Oz to American Idol runner-up Adam Lambert to a young gay friend, he had no idea who Garland or even Liza Minnelli were. In a New York Times article from 2012 questioning whether or not Judy’s raw talent and appeal will live on amongst gay men, Robert Leleux wrote that he “weeps for his people” when his thirty-something gay male friend says that he doesn’t consider himself a Garland fan and merely remarks that “she was good in The Wizard of Oz” (one of the most seen films in history). Leleux himself had been enchanted by Judy for his entire life. “Judy at Carnegie Hall was the soundtrack of my childhood,” he wrote. “As any fan can tell you, it’s Garland at her swaggering best: glamorous, triumphant and almost superhumanly resilient. It goes without saying that such resilience held enormous appeal for gay men.” When he asked his friend if Judy is still considered a gay idol, he commented that he doesn’t see what Judy Garland has to do with being gay anymore, but does describe the gay following surrounding contemporary female trainwrecks like Whitney Houston, Lindsay Lohan, or Britney Spears. “Some gay guys do seem to like that kind of thing,” he said. In response to questions about Rufus Wainwright’s 2006 recreation of Judy Garland’s Carnegie Hall album, his friend remarked, “If that’s what he wants to do, great. It’s just not my idea of being gay. Today gay can be anything.” Judy Garland might not resonate with all gay men, but it’s the fact that she was claimed as a gay icon during a tumultuous time in history when the gay community was beginning the fight for equality that has led to her status as not only a gay icon, but a pop culture icon. Today gay can be anything, but 50 years ago, it could not. For many, Judy felt like one of the only outlets where gay men could truly be and feel like themselves. She might not have had a single thing to do with the actions or the politics of the gay rights movement, but her omniscient presence was always there as a source of inspiration. Her impact is undeniable, and she will live on regardless—a biographical film starring Renée Zellweger as Garland, Judy, is set for release this fall.

|

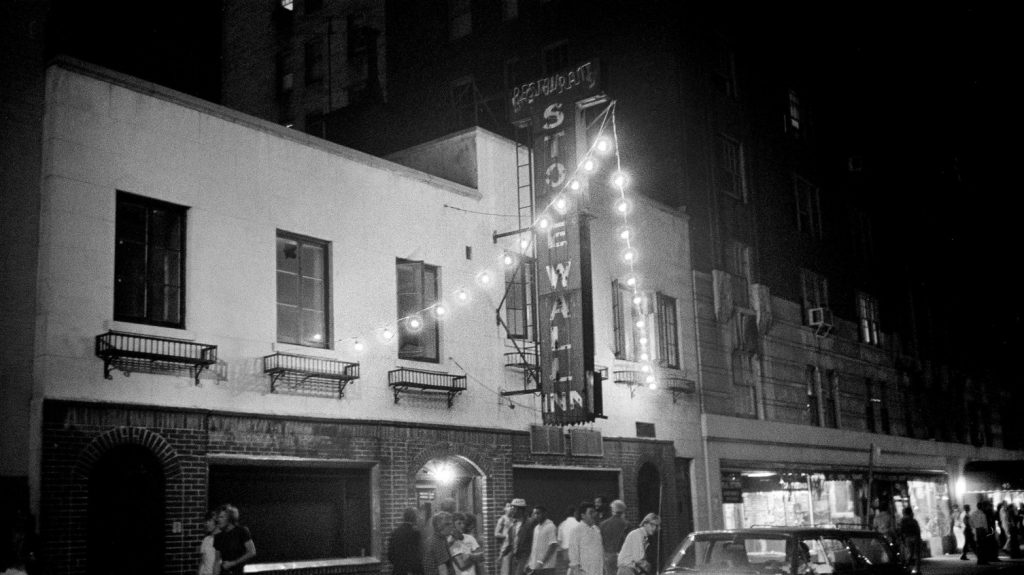

| The Stonewall Inn, in Lower Manhattan's Greenwich Village, was the site of the legendary riots in the early hours of June 28, 1969 that would begin the modern gay rights movement. (Photo: CNN) |

Judy respected gays, but she had no real connection to them.

ReplyDeleteThe Stonewall Riots were not triggered because of Judy's death and people in the know said that.

Judy, however, connected with ALL people in some way because not only was she (and still is) a star, but her life was both happy and sad in many ways and in the end, she was wanted and unwanted.

So it was easy to connect dots that weren't there between Judy and gays.

George Vreeland Hill

Pretty sure I made clear that it's gays who have a connection to Judy, not necessarily the other way around. There is definitely a link between gay men and Judy Garland, which is especially evident in popular culture. Judy was embraced as an icon by gay men, a minority group who have faced centuries of oppression. The dots are there, whether you can see them or not.

Delete